Background: Kabaleega was born on June 18, 1853 to Omukama KamurasiMirundiRukanamarwaKanembeKyebambe IV of Bunyoro-Kitara. His mother was a Muhumakati called KanyangeNyamutahingurwaAbwoli of the Bayonza clan. He ascended the throne in 1870 at the age of 16 as the 23rd Omukama from the Babiito Dynasty following the death of his father. He chose the throne name Cwa II after Omukama Cwa 1 Ente-Ankole Rumoma-Mahanga whose stories inspired him as a child. He was also later named Yohana (John) upon being baptised in captivity.

Kabaleega’s name was derived from her mother’s background as a girl from Buleega. Thus, her child by Kamurasi was called ‘Akaanak’Abaleega’ (literally ‘a kid from Buleega’), which was shortened to Kabaleega. His mother, KanyangeNyamutahingurwaAbwoli – a stunningly beautiful lady who became Kamurasi’s wife after the Abarusuura had acquired her as a booty during one of their forays in the area.

A member of the Bayonza clan, Kanyange was a daughter of one of the kings of Buleega (in present-day DemocraticRepublic of the Congo - DRC). Indeed, her name was symbolic of her beauty: Kanyange (from enyange – the egret) and Nyamutahingurwa (a bele who can easily be noticed and admired by any man).

As a child, Kabaleega grew up in the conducive environment of Tooro in Mwenge county, under the care of his maternal uncles, one of who was the chief of Tooro. As a boy, Kabaleega was fond of hunting, especially inNyakasura on the foothills of Mt Rwenzori.

Kabaleega spent much of his childhood away from the centre of Bunyoro power, living in Buleega in present-day western Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) during an uprising that threatened to topple his father. When the uprising was finally put down, Kabaleega returned to Bunyoro where he came of age.

Education and training: Kabaleega was a well-groomed prince, who underwent rigorous training and tutorship. He was a product of Galuhuma University – Bunyoro’s premier informal education institution. Located at Mukunyu hill in Mwenge county (where present-day Butiti PTC stands), Currently, Mwenge is a county of the Kyenjojo district in Tooro kingdom.

Galihuma was a centre of excellence in social services like education, health and administration of the kingdom. Children of the royals and chiefs were taken to Galihuma to learn official language of the empire, etiquette (acceptable behaviour), culture, education, health, human medicine, history, ideology and patriotism, diplomacy and administration.

It was a kind of political school where the princes were sent to learn the art and the language of government. The official king’s language was called Oruhenda – a variation of Runyamwenge sub-language. This was the language spoken at the palace, by kingdom officials and members of the royal family. The Bahenda were the expert at the Bunyoro culture and language.

However, upon coming of age, princes would be recalled to the palace for further training and scrutiny with a view to identifying the potential heir. It was through this process that OmukumaKyebambeKamurasi identified Kabaleega and Kabigumiire as the potential heirs.

Accordingly, he entrusted them to his brother, prince KamihandaOmudaya, with the task of refining the duo and, finally, selecting the heir apparent. In fact, it was Kamihanda who educated the two princes on the history of Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom, right from the Batembuzi to-date.

It is equally important that Kabaleega, like his brother Kabigumiire, underwent rigorous military training with the recently formed standing army called Abarusuura. They were also assigned specific military duties at an early age.

Character and personality: As a trained soldier, Kabaleega was courageous, single-minded, and sympathetic to the common people. However, the likes of KamuhandaOmudaaya viewed him as short-tempered, headstrong, proud and opinionated - ironically, the the very reasons why Kamurasi preferred him! Kabaleega, nicknamed “EkituleKinobereAbeemi”, was indeed intolerant of rebels. One by one, he punished rebellious royals and their supporters.

For example, he sentenced Prince Komwiswa to life imprisonment and sent Prince Rujumba to Mwenge to look after his (Kabaleega’s) cattle. He also put to death one of his sisters. This was after he had defeated the Chope-based rebels.Kabaleega’s other praise names “Ruhigwa”, “Rukolimbonyantalibwamugobe”, and “RwotaMahanga” – just to mention a few – testified to his indomitable, never-say-die character.

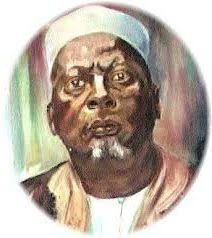

Physical appearance: Kabaleega was physically striking. He was about 5ft 10” tall, with a light complexion. He had very large eyes, a broad but low forehead, high cheekbones, a large mouth, and with white teeth. He was immaculately clean and well clad, usually in bark cloth striped with black.

As a military man, Kabaleega was energetic, often walking on his own foot, instead of being carried on the shoulders of a man, as was the custom with kings and chiefs elsewhere. He found the sedentary life of the palace most irksome but found pride in going upcountry to supervise the training and war readiness of his soldiers.

Language proficiency: Kabaleegaspoke Runyoro-Rutooro and was fluent in Sudanese Arabic, English, Luganda, Lugbar, Alur, Acoli, Langi and, perhaps a smattering of French. In public he preferred Runyoro and the aid of an interpreter.

Diet and hobbies: Kabaleega is said to have lived on a repetitious diet of veal boiled with bananas, millet bread and porridge, banana beer and amacunde(whey/skimmed milk). It should be noted that in Bunyoro-Kitara a varied crop-based diet was eaten only by the common people, for the nobles their food came from cattle products. In his free time, Kabaleega used to play omweso (the board game).

CONTRIBUTIONS OF KABALEEGA TO BUNYORO

1. FATHER OF BUNYORO NATIONALISM

Kabaleega infused into his people an overwhelming desire to fight desperately to retain their liberty and to reunite the kingdom of their ancestors.To a kingdom which had once been the dominant power in the Great Lakes region and whose rulers were descended from the gods, the avaricious attacks of these upstart kingdoms on their parent were regarded as sacrilege.

Even after the defeat and exile of Kabaleega in 1899, the Banyoro kept the flames of Bunyoro burning. The Banyoro formed the bulwark of resistance against British colonialism. They blamed the British for restoring the Tooro kingdom, which Kabaleega had reconquered; for allowing Buganda and Ankole to expand at their expense; and for forcing them to live under the rule of Baganda chiefs appointed by the colonial government, andRuganda was employed as the language of administration.

This resentment climaxed in the Nyangire Revolt of 1907, which was a rejection of Buganda’s sub-imperialism but primarily was a passive revolt against British rule. The revolt was suppressed, and direct colonial rule was imposed on the Bunyoro. This was shortlived, as in the long run, the Banyoro succeeded in having Baganda agents withdrawn in exchange for guaranteeing the peace in the region.

The Banyoro also saw the British as their enemies, powerful protectors of their ancient rivals in Buganda. In 1921, Banyoro nationalists formed a political group called the Mubende Bunyoro Committee (BMC), which quickly became the kingdom’s most popular political party. Its demands included the return of the “Lost Counties” and secession from British Uganda. The British treated the kingdom as a conquered territory until 1933 when Omukama Sir Tito Winyi finally signed a protectorate agreement.

The territorial dispute between Bunyoro and Buganda acquired renewed importance when Britain prepared Uganda for independence. In 1933, the colonial government, satisfied that the Banyoro had decided to accept the political reality, signed the Bunyoro Agreement with Omukama Winyi IV and his chiefs, by which Bunyoro district was officially recognised as the Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara.

The Banyoro regard this recognition as a validation of their claim to have presided over a Kitara empire. The agreement also ended the era of direct colonial rule from Kampala. The Bunyoro Agreement of 1955 formally ensured that the Omukama (king) was only the titular head of his kingdom.

In 1961, Tito Winyi refused to attend a constitutional conference until the British authorities resolved the conflict. The Baganda refused to negotiate, setting a crisis as Bunyoro moved toward secession and prepared for war. British mediation produced an agreement to hold a referendum on the “Lost Counties”, finally allowing Uganda to achieve independence in 1962.

On November 4, 1964, the inhabitants of Buyaga and Bugangaizi voted to return to Bunyoro. The conflict again became a crisis when the Buganda government refused to accept the results of the referendum. Banyoro soldiers gathered in Hoima and prepared for war, but the dispute quickly lost importance as even more serious threats menaced the kingdoms. The Uganda government, dominated by non-Bantu northern tribes, instituted laws to curtail the kingdoms’ authority.

In 1966, the government abrogated their autonomy statutes and, in 1967, abolished the kingdoms as administrative units. Banyoro nationalists, enthusiastically supported the overthrow of the hated government in 1971 by Colonel (later General) Idi Amin Dada. Amin’s new government, a brutal dictatorship dominated by Amin’s small northern Muslim tribe, the Kakwa, soon lost all support in Bunyoro. In 1972, Banyoro leaders, sickened by the excesses of the Amin regime, called for Bunyoro secession, but the movement lost momentum as Amin’s henchmen systematically eliminated its leaders (Munahan, 2002; 1429).

In 1967 the government of Milton Obote abolished all the Ugandan kingdoms and pensioned off the kings, but in 1993 the government of Yoweri Museveni restored the kingdoms. On June 11, 1994, Prince Solomon GafabusaIguru was crowned the 27th Omukama of the Ababiito Dynasty of Bunyoro-Kitara. The Banyoro are engaged in what they call the "Rebirth of Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom" in the context of their reduced circumstances.

The infamous Amin regime, finally overthrown in 1979, gave way to a series of weak, unstable Ugandan governments. A large resistance movement arose among the southern Bantu peoples of former kingdoms of the southwest, led by Yoweri Kaguta Museveni. When Museveni took control of Uganda in 1986, relative peace and democracy permitted the rebirth of Bunyoro nationalism, based on demands for the restoration of the kingdom.

The independence of Uganda in 1962 was welcomed by the Banyoro, but they remained unhappy because of the several lost counties; only the Buyaga and Bugangaizi were restored to them. The kingdom reluctantly agreed to accept autonomy and semi-federal status within Uganda.

A more radical minority advocated the secession of Bunyoro from Uganda, arguing that the kingdom’s inclusion in the multi-ethnic state had brought it only terror, death and destruction. In July 1993, the government allowed the partial restoration of the kingdom and the enthronement of a new Omukama, Solomon GafabusaIguru, a grandson of Kabaleega and the 27th monarch of the Babiito dynasty.

In September 1993, nationalists demanded the restoration of the kingdom’s traditional boundaries, including the Mubende area of Buganda, the Lost Counties.The first national elections in 16 years were held in Uganda in April 1996. The majority of the Banyoro supported President Museveni, fearing the chaos and violence of the north of the country. The vote generally split along regional lines in Uganda, with the Bantu south supporting Museveni, while the Nilotic north supported opposition leaders.

For decades, the Banyoro had been among the poorest of Ugandans, but in the 1990s they experienced a resurgence due to a new emphasis on cash-crop production by small-scale farmers. New prosperity and partial restoration of the kingdom fuelled demands for greater autonomy and for real political power for the new omukama.

2. GLORY OF BUNYORO

During Kabaleega’s reign, save for the reign of IsazaRugamban’Abato and NdahuraKarubumbi, Bunyoro-Kitara reached its apogee (period of glory). Aided by many hired Langi war bands, the army expanded Bunyoro for Kabaleega, whose motives were to revive the former glory of the empire, to obtain more grazing land for cattle, which was very important in the economy, and to gain control of the Katwe salt deposits in Tooro.

In 1875, the Barusuuraoverthrew Nyaika, the King of Tooro, and the breakaway kingdom was reunited with Bunyoro. Nyaika’s children were carried away prisoners into Bunyoro, except the eldest son, Kasagama and his mother who fled to Ankole. Rwanda, Ankole and Karagwe were successfully raided and forced to pay tribute.

Kabaleega also reclaimed several former parts of Bunyoro which had been annexed to Buganda, so that Bunyoro doubled in area under the first 20 years of his rule. Even more remarkably, Kabaleega’s was the first lengthy reign in centuries during which Bunyoro was free of internal rebellions.

In the north, Chope was conquered. The Nilotic-speaking communities beyond the Nile and the Acholi were forced to pay tribute. Buganda was not itself spared. At the Battle of Rwengabi, Kabaleega defeated the Ganda army, and some districts of Buganda were occupied and 20,000 Baganda were enslaved.

In fact, his aim was to recover the former Bunyoro Kitara Empire. The boundaries of his kingdom were as follows: West: Lake Edward, Busongora, Ituri Forest (present-day Democratic Republic of Congo), and stretching from Buleega and Butuku; North:Equatoria Province (Sudan); East: Lake Kyoga, Busoga, Bunyara on River Sezibwa, the Buganda boundary with Bulemeezi and Singo; South: Ankole bounded with Buzimba and Buhweju counties.

It’s probable Bunyoro would have expanded further, and at the expense of Buganda, which was ruled by a weak Kabaka Mwanga, if the British had not invaded the region, and taken sides with Bunyoro’s enemies in the late 1890s. He was proposing to attack Buganda, and therefore he had erected his residence at MukaihaKinogozi, but the arrival of the British thwarted these plans.

On the other hand, these foreign campaigns were embarked upon to heighten the prestige and the coercive power of the state, to bring in booty to reward followers, and to provide new tax resources and offices to be redistributed.

Royal absolutism increased as competition for royal favour became institutionalised, and centres of opposition were removed, primarily through the execution or destitution of most hereditary chiefs. Kabaleega made innovations in the structure as well as the personnel of the state.

3. REGIONAL SUPREMACY

As the supreme head of state, Kabaleega used to chair meetings of the House of Kings in the greater Bunyoro-Kitara Empire under the Nyakahuma (referred to as Nakayima) tree in Mubende. The kings would meet at least three times a year at regular intervals. Referred to as Kac in Luo, this tree was a symbol and instrument of national unity. Each king came with troops of the imperial army of Bunyoro-Kitara.In the 1890s, Tito Winyi, then a teenager, accompanied his father, Kabaleega, who presided over the extraordinary meeting. After the meeting, Kabaleega returned to Lukungu, his new capital, and Mwanga went to Lututuru/Agoro.

4. ESTABLISHMENT OF A STRONG, CENTRALISED STATE

Kabaleega developed a unique, strong centralised state structure that delegated powers and had checks and balances. He occupied the apex of a graded hierarchy of territorial chiefs, ofwhom the most important were the county chiefs.

Thus, Kabaleegawasthe political head of the kingdom, enjoying absolute authority over his subjects.He was the head of government and ruled his people indirectly through a hierarchy of chiefs. With this hierarchical arrangement the king’s messages used to reach at the grassroots very fast.

In the system of government that he created,authority flowed from him in descending order to a hierarchy of territorial administrators and palace officials who had specific functions. There were at least 14 levels in Kabaleega’s system of government:

1)Territorial administration, which had three three grades of chiefs:

Abakamab’Obuhanga orB’Amasaza– were the county chiefs. They were the first grade who were appointed by the Omukama to rule over the different counties which often differed in people, custom, dialect and environment. These chiefs had Endabaraba, deputies, who acted in their name either at the palace or in the counties.

These chiefs were the Omukama’s special advisers and protectors and were, to all intents and purposes, united as blood-brothers.

Abagomboroziwere administrators of amagomborra (sub-counties). These formed the second-grade chiefs. They were appointed by the Omukama to rule the divisions of the counties.

Abatongole (also known as Abakuru b’Ebitongoleadministered villages, which were sub-units of a sub-county).

Abakurub’Emigongo (headmen): They were the head of estates and/or local geographical units of a village, comprising of a geographically limited cluster of people. The Batongole and Bakirub’Emigongo formed the third-grade chiefs.

2) Royal estate administration

Amacumug’Omukama (royal stewards): TheAmacumug’Omukamawere the royal stewards responsible for the administration of the royal estates. They were appointed by the Omukama to rule the lands and estates that belonged to the Abago, royal consorts, and Ababiitokati, princesses, who were nominally in charge of the areas concerned. For instance, Buruli county was traditionally governed by Nyangoma, a princess. So was Busongora, which was a domain of princess Koogere.

These lands and estates were scattered over the kingdom and their administration and defence were the direct responsibility of the royal stewards on behalf of the Omukama. These stewards were the equivalent of the sub-county chiefs. They may have provided a counterpoise to the sub-county chiefs of the territorial administration in the event of a rebellion or succession war.

3) Abakungu (headmen): Below the royal stewards were the Abakungu, headmen, who administered the villages and estates of the royal consorts and princesses. The headmen in both the territorial administration and royal estates were the link between the people and the chiefs or the royal stewards.

4) Abakurub’Enganda (clan heads): Within each system of government were Abakurub’Enganda(clan heads). Each clan has always had its own head elected by all of its members. All matters pertaining to inheritance fell within their jurisdiction and they advised the Omukama accordingly. When a county chief died, it was the duty of the clan head to bring the heir before the Omukama for confirmation in his appointment.

5) Abakurub’Emirwa (advisers on ritual and regalia of the kingdom): The clan heads selected the advisers on ritual because many clans had hereditary duties in the palace. The association of the clans with the territorial and palace administration contributed to the stable and orderly government in the kingdom.

6) Abakurub’Ebitebe (Counsellors): Known asAbajwarakondo(the Crowned Order or Sacred Guild), these members were counsellors. They were invested by the Omukama for distinguished services rendered to the kingdom. Their offices were hereditary if the Omukama wished.

7) Orukuratorw’Omubananu (Cabinet): Before parliament was summoned, theRukuratorw’Omubananu(Cabinet) met to decide in secret all matters of policy and the agenda for discussion by parliament. The members of the Cabinet were the Omukama, Mugema(head of the councellors), Bamuroga(the principal chief who acted as regent when the Omukama died and, until another king was enthroned, had charge of the royal tombs), county chiefs, and a few other people of importance.

The Omukama was also chairperson of several courts and tribunals to settle public, private and domestic affairs. Later, the office of the Omuhikirwa(Prime Minister) was established by Kabaleega’s father and predecessor, Omukama Kamurasi, to head the civil service of the entire Kingdom. Kabaleega strengthened this new office, which symbolised the growing centralisation of power.

In 1887, he appointed NyakatuuraNyakamatura as prime minister, owing to his political competence and military prowess. A former slave, Nyakamatura had been the only Mwiru (commoner) among Omukama Kamurasi’s county chiefs. Kabaleega had retained his father’s premier, Kategora, for the first 16 years of his reign, before he was poisoned.

8) OrukuratoOrukururw’Ihanga (Parliament): The Office of the Omuhikirwawas supplemented by the Rukurato – the supreme legislative body of the land. Abbreviated as Orukurato, the parliament was an assembly of all the senior chiefs and officials from all over the kingdom who met three or four times a year, according to the necessity and at the discretion of the Omukama.

Kabaleega appointed an eminent man from each of the clans (72 at the time) to represent it in the Rukurato, which was chaired by the Omutalindwa (Speaker), who was also appointed by Kabaleega. Itwas for this reason that this body came to be known as the Rukuratorw’Ensanjuna babiri (The Council of 72”).It was composed of the Omukama, the county chiefs, counsellors and other officials of high rank. It was presided over by by the Omutalindwa(Speaker). Also, Kabaleega nominated an eminent person called a Mujwarakondo (Coronet wearer) from each sub-county to represent it in the Rukurato by virtue of his excellent services. These Bajwarakondo(plural) wore a string of beads around their necks as a sign of distinction. Their homes were a court of sorts.

9) The Royal Council: In addition, there were many important chiefs who held land under the district chiefs by virtue of some office, either within the royal enclosure or in the capital, which they held for the king. Their offices were hereditary in their clan though it was not necessarily the eldest or any son of the dead chief who succeeded. The following list of 15 gives an account of some of these:

a) TheBatebe: Among the most important of the omukama’sadvisers the Kalyota (“official sister”, “ritual sister” or“queen sister”). The duo represented the authority of the Omukama within the royal clan, effectively removing the king from the demands of his family. They are chosen for their vast experience and knowledge of cultural norms.

Originally called theRubuga, and currently called the Batebe, the Kalyotawas forbidden to marry or bear children, protecting the king against challenges from her offspring. Her duties include instructing members of the royal family in palace etiquette. She also serves as a counsellor to the King’s subjects on cultural norms including marriage.

During Kabaleega’s reign the Batebewas a kind of chief. She held and administered estates, from which she derived revenue and services like other chiefs. She settled disputes, determined inheritance cases and decided matters of precedence among the Babiito women (princesses). Princess Kabatongole was the Batebe during Kabaleega’s reign.

b) The Okwir: Like the Batebe, the Okwirwas the Omukama’s “official brother”. He was (and still is) the head of the Babiito, the Babiiti (royal clan). In Buganda, he is called Ssabalangira and in Tooro, the Omusuuga. were the Okwir) (and

Picked from the uncles of the Omukama, theOkwir assisted the new Omukama in governing the kingdom, who now served all subjects of the kingdom, the Babiito and non-Babiito alike. During the enthronement of a new king, the Okwir, among others, superintends a mock battle at the palace entrance fought between enemy forces of a "rebel" prince and the royal army.

As a test of king’s divine right to the throne, he calls on the gods to strike the monarch if he is not of royal blood. On passing the test, the king is permitted to sound the sacred drum, as his forefathers had done. He is then blessed with the blood of a slaughtered bull and a white hen.

c) Omugo’s Office: The Omugo - Omukama’s official wife or queen – had important matters to handle in the kingdom. With her office in the Karuziika (palace), the Omugo superintends over matters pertaining to women, children, and the poor lot.

d) Nyin’Omukama (Queen Mother): The Nyina Omukama (the king's mother), too, was a powerful relative, with her own property, court, and advisers within her designated territory. Kabaleega’s mother, KanyangeNyamutahingurwaAbwoli, was revered by everyone, including Kabaleega himself. She was perhaps the only female whose counsel Kabaleega could not dare go against. During the British invasion of Bunyoro, Kanyange rallied troops for war.

KanyangeNyamutahingurwa is revered as Bunyoro’s Joan of Arc. Joan was the brave woman of Europe who, garbed in male battle attire, so valiantly fought in the siege of Orleans, 1428AD. She discomfited the English in the celebrated battle of Pietz and almost singly sat Charles VII on the throne. So brave was Joan that in the year 1431, her heroism caused her premature end.She was burnt alive for it was put about that her prowess was so supernatural that it could only be the caused by sorcery!

But she was afterwards invested with a halo of glory and her great deeds are now cited in history books as examples of supreme heroism. In 1920, she was canonised, that is, acclaimed officially as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church! In the same vein, Kanyange, the illustrious mother of Kabaleega, rallied troops for war. It is important to note that during this decade-long war, women, including Kanyange, rendered support to the sustenance of the most honourable cause.

According to Sir Tito Winyi, whose pseudonym was K. W. (meaning Kabaleega and Winyi), this struggle would probably not have lasted that long if it were not for this support. Bunyoro history proudly chronicles the supreme emotional and physical heroism of women like KanyangeNyamutahingurwa as Europe does of Joan of Arc or Hamid Begum among other notable Muslim heroines. She went down fighting, hence a heroine.

9) Orukuratorw’Omurugo (Court of the Royal Enclosure): In this forum, the Omukama settled disputes between members of the royal family and the commoners.

10) OrukuratorwaBarwara (Court of the Kingdom): Here, the Omukama settled disputes between any of the people who lived in the kingdom, whether they were chiefs, freemen or commoners. He was assisted by his principal counsellors. Trials were held in public and witnesses were called to give evidence. Sometimes, if the Omukama was ill or busy elsewhere, the head of the counsellors or county chief took his place.

11) OrukuratorwaBamwenagaho (Court of the Eastern Tribes): In this forum, the Omukama gave audience to the Baganda, Basoga, Iteso, Bagishu and other tribes from the east.

12) OrukuratorwaKyakato (Court of the Pastoralists): Through this forum, the Omukama gave audience to the Bahima of Ankole, Karagwe, Kiziba, Rwanda, Burundi and other people from the south.

14) OrukuratorwaBinyonyi (Court of the Northern and Western Tribes): Here, the Omukama gave audience to the people of Bukidi (Langi or Bakidi), Acholi (Gaanyi), Madi, Lugbar, Lendu, Baleega and Mbooga.

NB: The people of Mbooga were originally Bahuma, who moved from Bunyoro, possibly in the latter half of the 17th Century. The Mbooga sub-dynasty was originally established by Chief Isingoma of the Maboro clan, who got into trouble with the royal house of Bunyoro and fled to the high grassland west of the Semliki river.

14) OrukuratorwaHamusanga (Court of the Royal Herdsmen): This session was held early in the morning at milking time. In it, the Omukama settled the disputes of his herdsmen before undertaking the main ceremonies of the day.

The Omukama ordered other tribunals whenever and wherever necessary to settle domestic and private matters. The effectiveness of this traditional system of government depended entirely upon the ability and the personality of the reigning monarch. If he was incompetent, he had to contend with other difficulties which made his task harder.These officials praised the Omukama while kneeling before him.

Administrative Structure: Kabaleega divided Bunyoro into 28 districts. These were:Bugahya (under NyakamaturarwaNyakatuura of the Bamoli clan); Busindi (under BikambarwaKabaale of Baranzi clan); Bugungu (under Mwanga rwaKanagwa of Bacwa clan); Kihukya-Chope (under KatongolerwaRukidi of Bacwa clan); Kibanda (under MasurarwaMateru of Bayonza clan); Bunyara (under MutengarwaIkamba of Babiito clan); Buruuli (KadyeborwaBantaba of Bagonya clan); RugonjoKalimbi (MutengesarwaOlalo of Babiito clan); and Bugangaizi (under KikukuulerwaRunego of Bairuntu clan).

Others were Buyaga (under RuseberwaRukumba of the Babiito clan); Nyakabimba (under Kato rwaZigija of Babopi clan); Kyaka (under NtamararwaNyakabwa of Bayonza clan); Mwenge (under MugarrarwaKabwijamu of Bayonza clan); Tooro (under RuburwarwaMirindi of Bayonza clan); Kitagwenda (under BulemurwaRwigi of Babiito clan); Busongora (under RukararwaRwamagigi of Baranzi clan); Buzimba (under NdururwaNyakairu of Baliisa clan); Buhweju (under NdagararwaRumanyweka of Bahinda clan); and Bwamba (under RukararwaItegiraaha of Bacwa clan).

They also included Makara [Busongora] (under KangabirerwaKajura of Baliisa clan); Mbooga (under IreetarwaByangombe of Basaigi clan); Buleega (under MuliwandwarwaOgati of Babyaasi clan); Ganyi (under AwichrwaOchamo of Babiito clan); BukidiLango (Kabaleega’s property under his direct rule); Kamuli Budiope (under NyaikarwaIgabura of Babiito clan); Arulu[Madi] (under AnzirirwaMidiri of Babiito clan); TesoKawero (under KamukokomarwaKatenyi of Bahinda clan), and Bunya [present-day DRC] (under RujumbarwaSalal of Baleega clan).

NB:Kabaleega revered BukiidiLango as the cradle land of the Babiito dynasty. It is for this reason that he never appointed any chief to administer this county, hence it was under his direct rule. Secondly, the county reportedly had the biggest market in the kingdom, hence Kabaleega might have wished to exercise his direct control over trade matters.

Thirdly, it would be unfair to accuse Kabaleega of nepotism, for only eight of these chiefs were his clanmates save for the fact that he entrusted to his mother’s pastoral clan the control of Kibiro salt mines.

It’s equally important to note that the Bunyoro expression rwain the names above refers to ‘son of’. Also, the plural form, rather than the singular one, of the clans has been preferred e.g. Babito (rather than Mubiito), Mubyaasi (rather than Babyaasi), etc.

ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE AND DOMINANCE

Until the advent of Kabaleega, Buganda had secured the monopoly of the Arab trade and had been able to obtain firearms and gunpowder. Kabaleega encouraged the Arabs to trade freely with him and so his army was no longer at a disadvantage when fighting the Baganda.However, during his reign, Kabaleega instituted economic reforms, which ensured Bunyoro’s dominance. This was done in five main ways:

Kabaleega demanded that taxes be paid in part in locally available commodities, which the kingdom could trade or redistribute among members of the ruling class;

He encouraged the widespread reciprocal gift-giving among kings, which was intended to promote good political and economic relations among their state. The gifts exchanged could be substantial;

The Omukama often dispatched royal merchants to trade on his behalf. These merchants usually combined the role of traders and diplomatic emissaries, and they were received as such.

He established a kind of royal trading diaspora by stationing members of the royal family or trusted agents in the foreign market towns to make royal purchases and to warehouse the Omukama’s exports and generally to act as brokers; and,

Finally, Kabaleega, followed by members of the royal family and state officials, enjoyed the privilege of purchasing goods from foreign merchants before they were offered to the public.

The main articles of trade were salt, cloth, coffee, tobacco, foodstuffs, livestock, pottery and iron (hoes, axes, knives and spears). Traders paid taxes on their goods, usually in the marketplace or on their income.

The payment of road tolls was also widespread. The rates were based on the value of the transit goods, the size of the caravan, or the power of the local ruler. In many places, road tolls were usually levied in one direction. The taxes were passed on the local chief to the king, with each level of power retaining a portion of the taxes.

Kabaleega’s reign is remembered as a time of economic prosperity. He emphasised wealth above everything else. Accordingly, Bunyoro flourished as a centre of long-distance trade. The reputation of Bunyoro ivory as the whitest, heaviest and largest in East Africa, attracted traders from the north (Khartoumers) and the Swahili Arabs from the coast. Bunyoro’s access to immense resources of ivory became its strongest advantage over Buganda, whose supplies were fast declining.

Ivory was also brought in from Alur, Buleega and Acholi, which were exchanged for guns from long-distance traders. Salt from Kibiro and Katwe were other precious commodities, which were under direct state control. Spears, hoes and other iron goods completed the list of exports.

Kabaleega wanted guns above all from long-distance traders; a musket worth one dollar in Zanzibar was exchanged in Bunyoro for ivory worth fifty pounds. Firearms enriched Bunyoro greatly increased its military power and served to cement political alliances. Bunyoro’s wealth, unity, and military strength enabled her to overcome the unprecedented challenges that faced Kabaleega when he came to power.

Sudanese slave traders fostered local conflicts for material gain and sought to make Kabaleega militarily dependent on their mercenaries. The Egyptian empire attempted to annex Bunyoro and replace Kabaleega with one of his rebellious cousins, while immense Ganda armies began attacking Kabaleega’s capital instead of merely raiding Bunyoro’s borderlands. Though Kabaleega did not impose a royal monopoly of long-distance trade, he ensured that what trade was not conducted by himself or his treasurer, Rwabudongo, was carried on by loyal favourites, such as Kikukuule.

Royal markets: During the reign of Kabaleega, some markets actually belonged to the Omukama. According to Nigerian historian G. N. Uzoigwe, there were about 50 markets in Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom prior to the arrival of Europeans.

a) Regional markets: The regional markets such as Katwe, Kasenyi and Kibiro, also in western Uganda, were well-established enterprises long before the northern Great Lakes region was penetrated by non-Africans. Each location was the locus for specialised production and sale, by a resident professional labour force, of a scarce resource in great features which were sensitive to attempts by indigenous, and later colonial, authorities to dominate strategic salt trade (Ref: Good M. Charles, 1970, “Markets in Africa: A Review of Research Themes and Question of Market Origin”, 1972).

Katwe Market: In precolonial Bunyoro, the great salt market at Katwe was a thriving hub of an “international” network of regional and long-distance trade routes over land and water, serving an area approaching 35 square miles. Salt was obtained there and then distributed elsewhere by means of barter, particularly in exchange for food staples and other resources found learning in the Western Rift Valley.

Its onsight “price” varied according to season fluctuations in supply (a function of climatic energy and political factors), with quality, and with distance from the source. Oral evidence and the observation of travellers such as Lugard certainly bear out that this trade was subject to the market principle, intermeshed with subsistence exchange networks, and was conducted without reliance on a currency, as the common denominator (Good, 1970; 154-162; 1972: 543-586)

b)Palace markets: At least four markets flourished around Kabaleega’s palace in Kahoora - as Hoima was originally called (the word Kahoora means market levy or dues). These were: Noberwemutwe – a market operated infront of the palace; Kibanya – a market at the back of it; Kidooka – a market at the westside of the pace; and, a fourth one operated at the east side of it. This one was controlled by EkitongoleEkihuuka of the Abarusuura (national standing army). Foreigners were forbidden from these markets. Trade in ivory and guns throughout the kingdom was strictly controlled by Kabaleega.

PARAGON OF A MODEL KINYORO FAMILY

Kabaleega married 138 wives. His senior or official wife Princess MalizaMukakyabaraBagaayaRwigirwaAkiiki, the elder sister of then King Kasagama of Tooro. She was popularly known as OmugowaBulera. BagaayaRwigirwaAkiikiwas the daughter of Omukama NyaikaKasungaKyebambe I of Tooro. She returned to Tooro after his capture and exile in 1899.

However, being a king, Kabaleega had other wives. His second partner wasAkiiki (Partner No. 1), NzaaheBagaya (the mother of Omukama YosiyaKitahimbwa, who ascended the throne when the British deposed Kabaleega on April 3, 1898. Kabaleega’sPartner No. 3 is untraced. However, one of his wives was a daughter of the king of Wakamba (in present-day Kenya). He is also believed to have sired Johnson (Jomo) Kenyatta, the first president of independent Kenya. While in exile in the Seychelles Islands, Kabaleega had three wives and at least two children.

Whereas, marriages of the Abakama of Bunyoro Kitara were restricted to daughters of specific and kings within the greater the greater Bunyoro-Kitara empire, Kabaleega went against this and married commoners, including Achanda from Acholi.

Special mention of Prince Jomo Kenyatta

Kabaleega is said to have sired Johnson (Jomo) Kenyatta, the founding father of Kenya. After his capture, together with Mwanga and nine other prisoners, Kabaleega was taken to Nairobi in June 1899. In Mont Plaisir (Marjorie) prison, the prisoners were joined by Olenana, the chief of the Masai. Meanwhile, Kabaleega, whose amputated right hand was yet to heal, was hospitalised in Gatundu military hospital.

The British assigned a Kikuyu maid to take care of Kabaleega. The relationship grew and led to a love affair and he impregnated here. She bore a son who was put in the custody of his uncle (the child would later become Jomo Kenyatta). Before he was moved to the Seychelles in September 1901, Kabaleega requested Olenana to look after the child when it was born. He had believed that all his children in Bunyoro had been killed by the British.

Upon getting to know of the boy’s birth, Kabaleega rued, “OgwoKinyaata; asangireObukamabuhoireho!” (literally, that late comer will eat crumbs since he was born after I had been deposed). However, Olenana gave him the Masai name Jomo. On the other hand, his maternal uncle under whose care the nurse was, named the boy Kamau (literally ‘of my mother’). The National Archives of the Seychelles entitled “Exile No. 3 – 1901 offer more evidence to this claim.

Kenyatta’s date of birth, sometime in the early to mid-1890s, is unclear. According to official records, he was born Kamau wa Muigai at Ng’enda village, Gatundu Division, Kiambu to Muigai and Wambui.

In honour of Olenana, when he became President of Kenya, Kenyatta directed that the Masai drum be sounded during major parliamentary sessions. Although 1889 is often cited as Kenyatta’s birth date, nobody, including Kenyatta himself, knows exactly when he was born. During his treason trial of 1952, on being the suspected leader of the Mau Mau rebellion, Kenyatta told the judge thus: “I do not know when I was born, what date, what month, or what year – but I think I’m over 50”.

Note the coincidence of names. Kabaleega was christened John when he converted to Christianity in 1907. Kenyatta’s first name – Jomo in Maasai – is Johnson (meaning “son of John)!Coincidentally, in 1914 – seven year’s after Kabaleega’s baptism in the Seychelles, Kenyatta was baptised a Christian and given the name John Peter which he changed to Johnson (others say Johnstone).

He again later changed his name to Jomo in 1938. He adopted the name of Jomo Kenyatta taking his first name from the Kikuyu word for “burning spear” and his last name from the Masai word for the bead belt that he often wore.

Indeed, when Uhuru Kenyatta won the 2016 presidential elections in Kenya, Omukama Solomon Iguru sent him a message of congratulation, which sparked a media flurry which Jomo Kenyatta being a descendant of the royal family Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom. This story appeared in The Standard of April 12, 2016, written by David Odongo, in which the story heavily relies on a similar story carried in The New Vision newspaper of Uganda.

Muhammad Kazimbirainelends credence to this story. In a personal interview, Kazimbiraine vividly recalls the Empango of Bunyoro Kingdom of 1965 (April 12), which was graced by all the regional heads of state – Julius Nyerere (Tanzania), Kenneth Kaunda (Zambia), Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya) and Uganda’s Milton Obote (Kazimbiraine, 2020).

Kazimbiraine, who was a student at Kabaleega Secondary School at the time, said Kenyatta used the occasion to clear doubts of his Kinyoro ancestry. Wearing a characteristic Kabaleega cap, Kenyatta spoke in Swahili, thus:“Mimi watuwotewananusumbua. Wanawulia, ‘Baabayakonaani? Baabayakonaaani?’ he said, as he asked for Kabaleega’s portrait. “Leeta pica yaKabaleegahapa! Woona shura yaKabaleeganamiimi! Sasaapaanataakakusikiyamuutuanawuliza, ‘Baabayakonaani? Baabayakonaani?’ Miimimutootowahapa!” he concluded amidst applause (ibid).

To paraphrase Kenyatta’s remarks, the Kenyan leader said he had been bothered by many people’s inquiries about his father. Holding Kabaleega’s portrait, he pointed out the striking resemblance between the two. He said he’s Kabaleega’s son and that from now onwards, people should stop asking about his identity, adding that he was a Munyoro). Kazimbiraine further intimated that Uhuru Kenyatta, the current President of Kenya, may have paid a secret visit to Omukama Solomon Iguru at the Karuziika (palace) recently. This claim, however, could not be readily corroborated (though he could not say with certainty).

A source close to the Karuziika (palace) also hinted about the close relationship prevailing between the current monarch and president of Kenya. President Kenyatta took care of Iguru’s sister, Princess Juliet KabacungaGafabusaAmooti when she was hospitalised in Nairobi. He also reportedly contributed to his medical expenses when she was admitted in India. (Kabacunga died on July 17, 2018).

All said, he mystery of Jomo Kenyatta, who became Kenya’s first president and fondly referred to by his admirers as the founding father of the nation, is still baffling. According to official records, Kenyatta was born Kamau waNgengi around the last half of the last decade of the 19th Century, to parents Ngengiwa Muigai and Wambui in the village of Ngenda, Kiambu county in British East Africa. Kenyatta himself was not sure of when he was born, as his parents were illiterate and there were no birth records or hospitals where young Africans could be born at in precolonial Kenya, but it is estimated to have been around 1889 to 1896 (Kenya Factbook, 1997-1998). If all this is true, the Babiito sub-dynasty in Kenya still lives on!

ENGENDERING POPULATION GROWTH

Kabaleega knew the importance of a big, healthy population in the development of Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom. Accordingly, he encouraged Banyoro to produce many children. He also encouraged foreigners to settle in the kingdom, at the same time discouraging migrations. Accordingly, the population of Bunyoro in 1894 – the year the British invaded Bunyoro – was 2.5 million people.

However, the Uganda Protectorate Census returns of 1911 and 1921 showed a population figure of 98,533 people then. Up to the late 1930s, the death rate remained high compared to the region’s birth rate. A study done by Shane Doyle in 1994 showed that people died because of excessive malnutrition.

To increase Bunyoro’s population, Kabaleega led by example. Though the number of children that Kabaleega sired is anybody’s guess, a conservative estimate puts the figure at 150. Yet others believe the number could be double that figure. Because of limited written literature during his reign, the records of his children are sparse, However, here below are his known children:

Sons/princes: Prominent among Kabaleega’ssons were Prince JaasiNyakimoso (the eldest, - 1899), Omukama YosiyaKitahimbwa, Omukama AndereyaBiserekoRuhaga II (1882-March 30, 1924), Omukama Sir Tito GafabusaWinyi IV (January 1883-1971), Prince John Nyakaana, Prince YakoboKarakaba, princes Hezekiah Rwakiswaza, ZakayoJaawe, AramanzaniMwirumubi, John Kabaleega (was childless), Kasohera, Katyetye, Binuge, SwiziniKaijamurubi (Kabaleega’s known last born among his children in Bunyoro).

Other princes were: Cosmas Kabeba, Edward Isingoma I, EriaKamugasa, Ernest Katyetye, Jaasi I, George Nyakaana I, Joseph Rwedeba, Kabakuba, Kabututuru, Kairagura, Kanyonyi, Kato I, Leo Nyakabwa II, Manyindo, Mark Kairumba, Michael Jaasi II, Muhammad Mukababanja, Musa Nyakabwa I, Mutikya, Isingoma II, PeteroNyakaana II, Yobo Karakaba, Yobo Rwanyabuzaana, ZabuloniKamugasa and ZeekereyaKasohera (these last two are said to be the only children of Kabaleega born of one woman).

Kabaleega’s sons also included: Alberto Mucokoco, ArajabKababebya, ArseniKakalema, Blasio Balyakwonka, Byambwene, Ezekiel Murusuura, Isaac Muntukwonka, Isingoma III, Kabafumu, Kabanda, Kabandi, Kabahembya, Kabugahya, Kabuzi, Kabusoga, Kafuuzi, Kagumali, Kanyabuzaana, Kafureeka, Kairagura, Kakahya, Kakibi, Kato II, K. Kato III, Katwire, Kawamara, Kiribubi, Kisagama, Kityokityo, L. Mpohote, Majegeju, Mulesa, Maturo, Mucope, Mujwara, Muhombooza, Mukurehya, Muporopyo, Musoke, Nicholas Kakyomya, Nyakaana III Basambagwire, Nyakaana IV, Nyakaisiki, Nyakakaikuru, P. Kamutole, Rwahwire, Rwomwiju, Wakame and Y. Kakyomya.

Daughters/princesses: Kabaleega’s daughters included Victoria Mukabagabo (Kitahimbwa’sBatebe/official sister), Jerulia Kaikara, the Batebe of Omukama AndereyaBiserekoDuhaga) and Louisa Mukabahaguzi, who was Sir Tito Winyi’sBatebe).

Other princesses were: AgiriMukabakwonga, Amina Nyangoma, Anastasia Mukabacope, Asa Nyangoma I, EseeriKamugoza, EsezaMukabasindizi, Eva Mukabakonda, Fatuma Nyakato II, Leah Dunyara, Martha Kahemwenkya, Martha Kasomi, Rosalia Mukabajumba, Rebecca Mukabacamba, Sania Nyakato I, Sarah Nyamayarwo, SefuroozaMukababaale, Sophia Mukabahuukya, TeziraMukabasindi, YudesiMukabakuba, YudesiKyonzira, YuniaMukabaganja, ZainabuKaniongorro, ZainabuMukabacanda and ZihuraKwebiiha.

The princesses also included: EseeriKahinju, FeresiMukabanyara, Martina Katengo, Rachel Mukababagya, RosiraMukabatasingwa, Sarah Mukabahemba, Serina Mukabadoka, Baitwoha, ZeresiMukabatalya, Kabajangi, Kabaheesi, Kabaramagi, Kabatwanga, Kabookya, Kafukeera, Kigali, Mukabafumu, Mukajwera, Mukabayamba, Mukababanja, Nyangonzinsa, Kasaya and Warwo.

Others were: Kababamya, Kababyasi, Kabajweka, Kabaganja II, Kabakuba, Kabaliisa, Kabahinya, Kabahwiju, Kabanyara, Kabarogo, Kabasuuli, Kahengere, Kasakya, Kabookya II, Kabayoyo, Kavogoro, Mukabagwera, Mukabasuuli and Rwomwiju.

CREATION OF STRONG, COHESIVE INDIGENOUS SOCIETY

Before Kabaleega came to power, the Banyoro were organised in strong clans, including the royal clan of the Kings, princes and princesses. Kabaleega used the policy of intermarriage and omukago (blood brotherhood) to unite the country. He himself, for example, married Achanda, a Luo woman, to act as an example. Historically, Bunyoro had been divided into four social groups:

Before the advent of Kabaleega, Bunyoro was organised into four classes or castes:

Babiito: Like their predecessors - the Batembuzi and Bacwezi - the Babiito, of Luo origin, were the royal or ruling family. They were the rulers and basically pastoralists.

Bahuma: The Bahuma were the aristocrats or middle class. Like the Babiito, they were basically pastoralists. The Bahuma regarded themselves as superior to all others; they originally regarded the Ababiito as part of the Bairu(farmers).

Bairu: The Bairu were the subject class, who constituted most of the society. They were basically commoner peasant farmers and greatly despised. However, they were the indigenous people and the entire society depended on their labour and support.

Bahuka: The Bahuka formed the fourth class. They were basically slaves, recruited through constant raids of neighbouring societies. They were the emancipated slaves.

However, when Kabaleega came to power, he abolished these classes and re-organised Bunyoro society.He encouraged intermarriage between the various clans and peoples of his empire, thus breaking down tribal-based loyalties. This created a considerable degree of social mobility.

During Kabaleega’s reign, clans tended to be in one place and the land was held by the clan for the clan’s benefit; rights of enjoying the use of the land Kabaleega granted to the clan members as long as they continued to occupy and cultivate the plots allotted to them.

By the twentieth century the Abahuma had disappeared as a distinct group and slavery had ceased to exist.Indeed, Kabaleega led by example, marrying a wife from at least each clan. He also encouraged a high sense of patriotism and loyalty by strengthening the custom of omukago – bloodbrotherhood.

In this bid, however, Kabaleega enjoyed only limited success because the majority of the Babiito and middle-class Bahuma resisted it. Rather than give in to his whims, they took up to arms while others migrated to other areas. The rest of Kabaleega’s reign was dominated by the struggle to limit the power of Bunyoro’s great families and to preserve his kingdom’s independence.

CHAMPIONING LITERACY AND EDUCATION

Much as he attended Galihuma University as a prince, Kabaleega realised the importance of a formal education. Accordingly, he was quick to ensure Banyoro learnt how to read, write and count (literacy and numeracy). Distrustful of the British-allied Church Missionary Society (CMS), Kabaleega invited the White Fathers to settle at Bukuumi Hill in Kakumiro, Bugangaizi.He encouraged these missionaries to embark on the education of Banyoro. The establishment of Bukuumi Secondary School, and other institutions that followed later, was because of Kabaleega’s vision.

Indeed, Kabaleega sent his 10-year-old son Prince UmfraenaKabaleega (later Reverend) to London for formal education. is the other unknown price. Born to Omukama Kabaleega on July 18, 1876, Prince Umfraena was to rise to ranks to become Africa’s world’s traveller, lecturer and preacher.

Kabaleega entrusted the teenage prince to a British missionary/English trader called Carl Boum, who enlisted him inprimary school in London. The prince attended Oxford and Cambridge universities before he began two tours around the world.

Aged 40 years, Prince Kabaleegatwas sent by the British to the United States in 1916 to recruit African-American to return to Africa and develop the continent. Hetravelled to and lectured in Chicago, Illinois, Houston, Texas, Gulf Port, Mississippi, New Orleans, and Los Angeles between 1916-1919, preaching African Redemption to Blacks in the USA.

His activities, however, attracted the attention of the Government of the United States of America. Soon, the Federal Bureau of Investigations initiated investigations into his activities.In a letter addressed to Mr R.R. Morton, the Principal of Tuskegee Institute, dated April 23, 1918, Kabaleega stated that had been active in recruiting African-Americans for resettlement which would now require the purchase of a steamship for implementation.

In this letter, he announced his plans for establishing the Black-Star Line. He stated: “I have plans by which means I will be able to raise a great deal of money from my race for shipping facilities providing that the Government of the United States will grant me the privilege of demonstrating the possibilities and opportunities of the resources of Liberia to my people. I believe within a short time, I can raise money enough from my people for the purchasing of a steam ship for the usage of this Government and to the credit of my race.”

This letter is dated a full year before the Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) launched in April 1919 of his plan for establishing the Black-Star Line - a steamship which was to be used for the purpose of resettling African-Americans on the African Continent.

PrinceKabaleega tried to develop his home area, Bunyoro. In March 1920, he founded the African Interland Missionary Society (AIMS) – also known as the Ethiopian Interland Interdenominational Missionary Society - with “Bunyoro, British East Africa” and New Orleans serving as its African headquarters and the American centre of operations respectively. He was the President of AIMS while his wife, Lena Kabaleega, was its secretary-general.

However, African-Americans hated him, suspecting him of being a British spy. Even when he was cleared by the CIA, he was limited in his ability to reach African-Americans on a large scale. He was also criticised for not articulating possible stock investment plans. And, because he had no access to a propaganda organ along the lines of Garvey’s Negro World, it’s understandable that his plans would fail.

In the end, Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) blacklisted him. A public notice in The Negro Worldof June 23, 1923 Page 6 entitled “Not Entertain Him!”, “All members in the United States are hereby notified that Prince Kabaleega has not been authorised to collect any funds from the members of the Umversa1 Negro Improvement Association to foster any plan which he may present to the divisions throughout the country officers must stage no meetings for the aforementioned PARENT BODY”.Finally, they plagiarised his idea of establishing the Black-Star Line.

Note that both princes attained Western education. Prince Kabaleega was a graduate of both Oxford and Cambridge universities while Kenyatta was a product of the London School of Economics.

PACIFICATION OF BUNYORO-KITARA KINGDOM

After the death of Kamurasi, Bunyoro was engulfed in a two-year fratricidal war of succession, between Kabaleega and Kabigumiire – bothfighting one another for the throne. In all, there were eight (8) claimants to the throne, the others being:

Ruyonga, who was Kamurasi’s cousin, was an unsuccessful claimant to the throne of Bunyoro-Kitara at the time of the latter’s accession. He subsequently took refuge on an island in the Victoria Nile in Chope. He died in 1881.

Kacope, was Kamurasi’s brother, who he edged out when he usurped the throne, yet he had regarded himself as the rightful successor.

Mupiina, son of prince Kacope.

Mpuhuuka, an elder brother of Mupiina. He had been an unsuccessful claimant to the throne at the time of Kamurasi’s accession. He was again unsuccessful in the assertion of his claim when Kabaleega succeeded Kamurasi. Mpuhuuka died sometime before 1876. After his rapture with Kabaleega, Baker produced Ruyonga as ruler of Bunyoro but Kabaleega nevertheless remained the defacto ruler of the kingdom. Ruyonga died in 1881.

Prince Komwiswa declared himself king of Chopein 1870 – something that incensed Kabaleega to find a panacea to this nagging problem.

Rujumba, who was Komwiswa’s younger brother, also claimed the throne.

This strife was prolonged and embittered by foreign intervention, mainly the Omugabe of Ankole, KabakaMuteesa I of Buganda and the ivory traders from Khartoum. Add to this the fact that though Kabaleega was the rightfulheir to the throne, most of the Babiito and the Bahuma middle class rejected him in favour ofKabigumiire.

Suffice to note, since the reign of Kamurasi, Chope – comprising the two counties of Kihuukya and Kibanda- had been a stone in the shoes of the kingdom. That’s why Kabaleegatasked General Rwabudongo to pacifyChope. In the ensuing battle of Kisembe, Rwabudongo smashed prince Komwiswaand his rebel fighters.

The captured Komwiswa was arraigned before Kabaleega who, rather than kill him, imprisoned him at KakindoBwanya. He was later moved to KasimbiBuyaga, where he was put under the watchful eye of saza chief Rukinzo of the Babyasi clan. On the other hand, Rujumbawas sent to Mwenge as Kabaleega’s herdsman.

Komwiswa was once more moved to Mpigwa in Buleega, where he remained a prisoner until Kabaleega’s overthrow. The British, having stumbled upon him in their campaign against Kabaleega, brought him back to Bunyoro. They made him a prominent chief in the post-Kabaleega reign.

Rujumba, who was also rehabilitated by the British, was the father of Prince KosiaLabwoni, the Kaigo (saza chief of Bujenje) during the reigns of AndereyaDuhaga and Sir Tito Winyi. Prince Kosiya is the father of Princess KabakumbaMatsiko.

Because the princes of Chope were always threatening to rebel, Kabaleega decreed that no Babiito (princes) should be made saza chiefs in the regions of their origin. He, therefore, appointed KatongoleRukidias the Ow’Isaza of Kihuukya (Chope) and Masuura, son of Materu, the chief of Kibanda (Chope) county.

PRESERVATION OF BUNYORO’S INDEPENDENCE

Kabaleega preserved Bunyoro’s independence by opposing foreign interference into Bunyoro’s affairs. He used both the stick and carrot approach to defend his kingdom against foreign invasion.

a) Succession war:Although Kabaleega had relied on several internal and foreign support, Kabaleega asserted his independence in the face of internal opposition especially ofwho troubled him throughout his reign. These rivals were from time to time assisted not only by the neighbouring rulers of Ankole and Buganda, but also by members of the Paluo and other Nilotic tribes living across the Nile to the worth of Bunyoro and the Dongolese slave traders operating in those areas.

KabakaMuteesaof Buganda, for example, had seen the succession war of 1870 as an opportunity of weakening the power of his country’s hereditary enemies by formenting strife and by endeavouring to secure the throne for his own nominee. That’s why he decided to support Kabigumiire and sent an army to his aid.

The Baganda found Kabaleega supported in considerable strength by the ivory traders, who had built themselves a fort. Though they were only armed with spears, the Baganda attempted to storm the position. The Arabs easily repulsed the assault with firearms. One of Muteesa’s favourite chiefs was mortally wounded and the Baganda inconsistently fled.

After a lot of soul-searching, Muteesa made a u-turn. He told Kabigumiire, who had fled to Buganda, that his presence was not wanted. He also congratulated Kabaleega upon his victory. Kabigumiire. retired to Cope county in present-day Kiryandongo District where Kabaleega’s ally, Nyakamatura, murdered him using the King’s spear called Kinegena.

Kabaleega inflicted a similar defeat to the Omugabe of Ankole’s army that had supported Kabigumiire. He even captured their commander, IreetaByangombe, who was to play an instrumental party in Kabaleega’s army and subsequent wars.

b) The Kheldive Ismail’s Equatoria Province Project

Kabaleega used military might to expand and consolidate his dominion. In this way, he was able to thwart the ambitions of the Kheldive of Egypt, who, through his European agents – Sir Samuel Baker, Charles Gordon and Emin Pasha - wished to found an equatorial empire based on the Nile and the Great Lakes – perhaps stretching as far as the Indian Ocean.

Kabaleega’s greatest success was in fighting off Egypt’s attempts to incorporate his kingdom into its Equatoria province. The threats first emerged in 1872, when Samuel Baker raised the Egyptian flag at Kabaleega’s capital prompting a series of violent confrontations over the following 16 years. At first, Kabaleega focused on containing the Egyptian garrisons established on his northern border. Later, as Equatoria weakened following the Mahdist uprising, he concentrated on obstructing the attempts of its governor, Emin Pasha’s, to open lines of supply and communication through Buganda.

Bunyoro had only recently formed direct trading links with the East African coast, and, having become the dominant trader of firearms and ivory in the region, had little to gain from a proposal that would re-establish Buganda as the local hub of long-distance trade. This policy hastened the collapse of Equatoria, but earned Kabaleega the reputation in Britain as a monarch who could not be negotiated with.

c) British imperialism

Just as the Egyptian threat evaporated, Capt. Frederick Lugard arrived in the Great Lakes region as the representative of the Imperial British East Africa Company, set on destroying Kabaleega. Encouraged by Christian converts in Buganda to see Kabaleega as an ally of militant Islam and a bastion of slave trade, Lugard restored Tooro’s independence and defended it with a line of garrisons.

Kabaleega’s attempts to again exert control over Tooro were viewed by the British agents who followed Lugard as evidence of his irreconcilability. In December 1893, a huge imperial army invaded Bunyoro, set on overthrowing Kabaleega and subjugating Bunyoro. What followed was one of Africa’s most destructive wars of colonial conquest. Kabaleega hoped that prolonged resistance would force Britain, like Egypt, to withdraw.

Quickly abandoning the strategy of frontal assault, Kabaleega’s forces launched a sustained guerrilla campaign, the tactics of which evolved significantly over the years. Bunyoro’s forces ambushed British supply caravans, learned to fire in volleys, adopted a scorched-earth policy, dug trenches to protect themselves from machine-gun fire, and secured the support of a variety of foreign groups, including Sudanese mutineers and Baganda rebels.

In 1899, Kabaleega was finally captured by a combination of Baganda and Indian troops. He was exiled to the Seychelles, and the Bunyoro throne passed first to his son, YosiyaKitehimbwa, who was deposed by the British due to incompetence in 1902, and then to another son, AndereyaBiserekoDuhaga.

The Banyoro had suffered heavily as the price of Kabaleega’s resistance. Their country was desolated. The British had, moreover, thanked their Baganda allies by giving them large tracts of land that had hitherto belonged to Bunyoro-Kitara, including the “Lost Counties” where many of the former Bakama are buried. These territories were formerly included within the boundaries of Buganda by the 1900 Buganda Agreement.

The tragedy of Kabaleega is that he had hoped to negotiate with the British as he had done with Emin Pasha at the time of Egyptian dominance. However, the British, misled by the Baganda and influenced by other considerations outside the immediate context of Buganda, persisted in regarding him as an implacable enemy.

Stripped of their salt monopoly and of outlying territories, the Banyoro remained less developed throughout the colonial period. They accused the British of trying to punish them for their unwillingness to accept protectorate status as did the neighbouring kingdoms. They were the outcasts of the colonial administration, victimised by the British and other tribes.

STRONG TRADITIONAL KINYORO FAITH AND RELIGION

Kabaleega refined the traditional Cwezi cult into a strong national faith. Therefore,the people of Bunyoro, far from being pagans, heathens or kaffirs, were intensely religious. They would pray to Ruhanga directly or indirectly through the other gods, for good health, longevity, prosperity, fecundity or fertility, peace and security, among others. They would even offer sacrifices – an equivalent of today’s tithes and religious offerings. No wonder, the Kingdom has a national prayer which up to now is unrivalled:

Esaaray’Ihanga Bunyoro-Kitara

Ai Nyamuhangaow’Igurulyera

Atuhaakasanaakootwabaingi,

AyahangireIgurun’Ensiebitagiranyomyo,

Ayahangireabantun’ebisoro,

Ebimera, ebinyonyin’ebihuka,

Ensozin’ebihanga,

Enyanja n’ebisaaru.

Nyamuhangaomuraramirwa,

Omutegerwaengaroniitaswara,

Nitukusiimahabwabyonaebirungiotuha –

omusanan’enjura,

ebyokulyahamun’oruzaaro.

Ai Kagabarugabiraboona,

Otugabireitungonyabahangwa. Kazooba ka Hangi,

nitukusabaotukulizeabaanabaitun’entegeigorookokere.

Ai Rukiraboona, nitukusabaohungukirreKabohabohay’Abalimwoyo,

Kandi ohigikeemihingoomubusindebw’endwaran’orufu,

ebidandin’ebijambuuka,

ebigasaigasa, amageegen’ebinyamangangana,

orufun’endwara,

amahembehamun’ebifaaru.

Otukingirizeekiiheky’enjara, omuyaga, orubaale, ihunga,

Okusandaarakw’amaizi, emisisan’enyamaiswakalyabantu.

Ai Ruhangaow’eriisolikooto,

nitukusabaotusensehoemigisayaawe,

Kandi otuheobwomeezinukwotwomeerenk’oburo

– enkooleihukurwa!

Nikikahabuke!

MODERN DIPLOMACY

Kabaleega wished to maintain healthy diplomatic relationships with neighbours and foreign countries. Accordingly, he appointed diplomatic envoys to many countries to safeguard the interest of Bunyoro-Kitara Kindom. Among these were Karubanga (Mengo/Buganda), Kasabe (Egypt). Kabaleega also encouraged foreign countries and entities to establish offices and stations in Bunyoro. These included the White Fathers (Bukuumi) and the Principality of Abbey (Gaanyi/Acholi county).

The Abbey-Principality:The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi was founded on August 25, 1883 on the frontier land of Tripoli-Fezzan (present-day Libya) in North Africa, with the approval of the French government. It was thus named in memory of the saintly King of France, Louis IX, who died in Tunis in 1270, during the second Crusade (Villate; 2006; 257-8).

By its constitution, the colony was independent and was known as the Principality of San Luigi, Dom HenricePacomez, a Spanish Benedictine, being elected as the first Prince Abbot. He died on February 10, 1884, and was succeeded by Dom Jose Plantini, who was killed the same year, on August 2, by the local population.

Dom Jose Plantini, the 3rd Prince Abbot, was driven out of the country with monks SeveroArrigni, Luis Ferratera, Antonio Voluppi and Marco Asvedo. They travelled through North Africa and Egypt to the Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara, arriving on the shores of LakeMwitanzige on March 15, 1885.

In 1896, Dom Loius Francois de Girardot succeeded Dom Mendoza as the 4th Abbot of San Luigi and the third Mukungu Order of the Lion and Black Cross (OLBC) in Bunyoro Kitara. They were greeted by Omukama Kabaleega who gave them a territory where the Abbey-Principality was established. Dom Mendoza received from the King the status of Mukungu, which is equivalent to the title of Prince.

In 1888, during the war opposing Kabaleega to British colonial forces, the monks returned to Europe. Prince Abbot Jose continued in exile the work of San Luigi, including the conferment of the Order of the Lion and Black Cross (OLBC).However, with the defeat and capture of Kabaleega in 1899, Dom Girardot took refuge in France (a Bunyoro ally at the time) and, on May 7, 1899, in front of the Mayor of Seine and Marne), he transferred his authority and title of Prince Abbot of San Luigi (Mukungu in Bunyoro Kingdom) and GM of OLBC to Bishop J. Rene Villatte (Villate; 2006; 257-8).

Thus, the survival of Principality as a sovereign state, was short lived. Plagued by disease and attacks by the local population, the remnants of the Principality reached Bunyoro, where Omukama Kabaleega established them. The Prince Abbot received then, from the Omukama, an equivalent to the title of Prince.

During the British invasion of Bunyoro, they returned to France, thus abandoning their State. The Order of the Lion and of the Black Cross continued to be bestowed, in exile, by the Prince Abbot. One of the duties of the members of the Order is the restoration of the independent Principality.

The defeat and exile of Kabaleega to the Seychellesmarked a loss of contact between San Luigi and Bunyoro that would last for over a century.Now in France, and with the hope that one day the Abbey would be restored, Prince-Abbot Joseph II appointed the young Frenchman Louis-François de Girardot (1869-1959) his successor on St Louis’ Day 1896.

Accordingly, Joseph II resigned in his favour on May 5, 1897. This appointment was legalised before the Mayor of the Commune of Seine-Port (Île-de-France), M. Eugène Clairet (who served as mayor from May 1896 to May 1900) and two witnesses. This legalisation by a French government official established the recognition of the Abbey-Principality by the French state.

However, the principality did not fare well. Disease was endemic, but more acute was the problem of the local Muslim population, who attacked the abbey, murdered the Prince-Abbot and drove the remaining monks into exile. Dom José Mendoza succeeded as third Prince-Abbot in 1884. He and what was left of his community eventually reached Bunyoro-Kitara, which is today one of the six kingdoms making up Uganda, and there were welcomed by the Omukama (King) Cwa II Kabaleega.

The Omukama consented to the re-establishment of the Principality within the kingdom of Bunyoro and bestowed upon the Prince-Abbot the title of Mukungu (translated as Prince-Governor), which is a chiefly title in Bunyoro. In 1888, Prince-Abbot José II was left the only civ Separate from that re-founded by the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch in 1891 which has been discussed elsewhere. cv Sometimes given incorrectly as “Makougos”.

In 2012 the present Omukama of Bunyoro recognised the present author as the successor to this title, he having previously been elected to the Prince-Abbacy by the Supreme Council of the San Luigi Orders (following the provisions of the 1954 Declaration on the succession to this office) in 2011. This followed an interregnum of some years after the previous incumbent, Prince-Abbot Edmond II (George Arvid Lyman) had died in 1998 without appointing a successor, at which point the power of election reverted to the Supreme Council.

Foreign relations:

The Abbey-Principality of San Luigi:On October 15, 1883, Prince-Abbot Henrice founded the Order of the Crown of Horns and the Order of the Lion and the Black Cross. Prince-Abbot Joseph II and four brothers – DomxSeveroArrigin, Dom LoiusFerratera, Dom Antonio Vollupi and Dom Marco Asvedo – arrived in Bunyoro-Kitara from North Africa via Gondokoro on March 15, 1885.

Dom Jose Plantini, the 3rd Prince Abbot, was driven out of the country with monks SeveroArrigni, Luis Ferratera, Antonio Voluppi and Marco Asvedo. They travelled through North Africa and Egypt to the Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara, arriving on the shores of L. Mwitanzige on March 15, 1885. Kabaleega warmly welcomed them.

In an act of generosity, Kabaleega granted them territory in the kingdom – in the county of Gaanyi (Acholi) – to be specific – to establish their Abbey. He also signed a diplomatic treaty with the Principality, where he conferred upon Prince-Abbot the chiefly title of Mukungu(Prince-Governor) of the Chieftainship of the Ancient Abbey-Principality of Sam Luigi (Fizzan).

In 1888, an epidemic of tropical fever claimed the lives of all the monks except Prince-Abbot II. Accordingly, he decided to close the Abbey in Bunyoro and return to Europe. Worse, the defeat and exile of Kabaleega to the Seychellesin 1899 marked a loss of contact between San Luigi and Bunyoro that would last for over a century.

However, this agreement still stands. After the restoration of Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom in 1994, this diplomatic relation was resumed. On January 25, 2012, Omukama Solomon Iguru I conferred the title on Prince-Abbot Edmund II. His regnal title is Edmund III.

EFFICIENT AND EFFECTIVE HUMAN RESOURCES POLICY

Much as Kabaleegacentralised power, he delegated authority was given precedence over inherited status, as commoner chiefs were entrusted with disciplining the destructive ambitions of royal kin. Herecruited tried and trusted officials with exemplary education, training and competence.

Accordingly, he displaced the provincial lords, with competent and loyal cadres drawn from both traditional and modern sources of authority. There were many important chiefs who held land under the district chiefs by virtue of some office, either within the royal enclosure or in the capital, which they held for the king. Their offices were hereditary in their clan though it was not necessarily the eldest or any son of the dead chief who succeeded.

The traditional government of Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom consisted of a hereditaryruler, or king (omukama), who was advised by his appointed councilconsisting of a prime minister, chiefjustice, and treasurer. Though the king's power was absolute he consulted in mostpatters a body of chiefs who were known as the Sacred Guild.

The following list of 15 gives an account of some of these:

Kabonerwa of Buligira. This man was the leader in all royal processions.

Oyo BiigomeRwaro, who imitated the actions of the king at feasts, beating his drum with reeds instead of rumsticks.

Mugema of Buchubya. By virtue of his office, this man took precedence of all chiefs who wore crowns, though he had no authority or judicial power over them and was not able to settle any lawsuit among them, for in such a case they had to appear before the king. This man belonged to the Babopi section of the Ngabi or royal clan, and the office went in rotation to each of the three divisions of that section, the Mugema, Zigija, and Kisoja. These men wore crowns even when not in office and were subordinate to the one who was in office.

Bamuroga of Kijagarazi. He was the principal chief and always acted as regent when the king was dead until the new king was appointed. He had also special charge of the royal tombs.

KikatoRubaya of Kikomagazi. This man had to provide the special gate for the kraal of the enkorooto (sacred herd of cows) and was in command of all the gate-keepers of the royal enclosure.

Kasumba of Bugahya. This man claimed to be a prince and to have come with the first king into the country. He also declared that he had the right to use an ivory door sill, like the tusk that lay before the doorway into the throne-room.

Kanagwa of Bugungu was keeper of an axe called Kiriramiro, which was used for killing people.

Muhaimi of Kihaimi in Bugangaizi was keeper of the drums. He belonged to the Bayaga clan.

Bwogi of Bugangaizi was keeper of Njagu, the royal clothing.

Kagoro of Ekibijo provided a girl who had to be in constant attendance on the king.

Muguta of Kyoka was said to have control over the lions of the country. Each year the king presented him with two cows, and he in return prevented lions from killing people and cattle. Women presented him with butter to smear on the lionsto keep them from attacking people.

Batalimwa of Kichwera was responsible for two horns of medicated water which he brought daily and anointed therewith the king’s head and chin.

Kyagwire of Kijingo was the priest of River Kihiira (Nile) and the waters of the country.

Nyaika of Pakaanyi had charge of the royal bugle. He was said to have come with the first king as a slave and blew a bugle for him on any special occasion. He announced to the musicians when the royal band should start playing.

Manyuruga Bungu of Kiyonga was a medicineman who prevented lightning from striking the royal houses.

Kabagyo of Mukyotozi was the maker of a special crown.

Katongole of Bulwa was a royal medicine-man.

Kadoma, the chief herdsman of the sacred goats, once upon a time stole a goat from the king and ate it. This was a criminal offence; but instead of being put to death, he was made to wear a bell round his neck and ring it before the king at stated times. This came to be regarded as a sign of chieftainship, and his descendants have been chiefs ever since.

Administrative system: Kabaleegaappointed chiefs at five levels: Mukuruw’Omugongo (local unit), Mutongole (village), Muruka (parish), Ow’Igomborra(sub-county) and Ow’Isaaza (county). Each saza chief has a few subordinates at various levels. A saza chief was entitled to a tract of land in the county, labourers, womenfolk, and cattle.

If the saza chief executed his duties well, he would remain at his post. If not, one night a party would be sent to levy execution. They would sorround his house, and confiscate everything inside for the benefit of the sovereign. Another chief would then be appointed and installed in his place. Every chief might be sent for to appear before Kabaleega, and the duration of their stay in the palace would depend on the prevailing circumstances.

PROMOTION OF TOURISM AND ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION

Kabaleega promoted tourism and protected the environment. Nothing exemplifies this better than the Royal Mile - a spectacular one-mile-long forest road - derives its name from Omukama Cwa II Kabalega (1853-1923) of Bunyoro-Kitara.

The Royal Mile is located on the southern side of the 8,255sq km big Budongo Forest Reserve next to Nyabyeya Forestry College. This Forest that lies at the edge of the Albertine Rift and is attached to Murchison Falls National Park in the south.

This wide forested track is a superb birding spot with many west and central African species, as well as a variety of sought-after key species. Migratory birds are present from November to April. About 360 species of birds are recorded in the total area, including the rare Puval’sIlladopses which is endemic to the region.

The Royal Mile

The road opens with a simple gate before sloping gently towards River Sonso in the middle of an expansive, natural symphony of hardwood trees rising high above the ground in what comes off like competition for the skies. This is what makes the Royal Mile one of the most ideal places in Uganda to have a guided birding tour. The terrain is flat, allowing for good on-foot travelling conditions for tourists.

Kabaleega used to frequent the forest, together with his queen for recreation; to perform cultural rituals; and to supervise the Abarusuura undergoing training. Reportedly, Kabaleega used this very road on his way to Lango as the British-led imperial army tried to capture him in 1894.

On the other hand, the Royal Mile was Bunyoro-Kitara’s local pharmacy. Kabaleega decreed that all known herbal tree species be gathered and planted on either side of this avenue. Accordingly, herbalists and medicine men would use the trees to cure all known diseases and ailments.

CREATION OF A FORMIDABLE MILITARY FORCE